Tag: Armenia/Azerbaijan

This week’s peace picks

There is far too much happening Monday and Tuesday in particular. But here are this week’s peace picks, put together by newly arrived Middle East Institute intern and Swarthmore graduate Allison Stuewe. Welcome Allison!

1. Two Steps Forward, One Step Back: Political Progress in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Monday September 10, 10:00am-12:00pm, Johns Hopkins SAIS

Venue: Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, The Bernstein-Offit Building, 1740 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036, Room 500

Speaker: Patrick Moon

In June 2012, the governing coalition in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had taken eighteen months to construct, broke up over ratification of the national budget. In addition, there has been heated debate over a proposed electoral reform law and the country’s response to a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights. Party leaders are once again jockeying for power, and nationalist rhetoric is at an all-time high in the run-up to local elections in early October.

Register for this event here.

2. Just and Unjust Peace, Monday September 10, 12:00pm-2:00pm, Berkeley Center for Religion, Peace, & World Affairs

Venue: Berkeley Center for Religion, Peace, & World Affairs, 3307 M Street, Washington, DC 20007, 3rd Floor Conference Room

Speakers: Daniel Philpott, Mohammed Abu-Nimer, Lisa Cahill, Marc Gopin

What is the meaning of justice in the wake of massive injustice? Religious traditions have delivered a unique and promising answer in the concept of reconciliation. This way of thinking about justice contrasts with the “liberal peace,” which dominates current thinking in the international community. On September 14th, the RFP will host a book event, responding to Daniel Philpott’s recently published book, Just and Unjust Peace: A Ethic of Political Reconciliation. A panel of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish scholars will assess the argument for reconciliation at the theological and philosophical levels and in its application to political orders like Germany, South Africa, and Guatemala.

Register for this event here.

3. The New Struggle for Syria, Monday September 10, 12:00pm-2:00pm, George Washington University

Venue: Lindner Family Commons, 1957 E Street NW, Washington, DC 20052, Room 602

Speakers: Daniel L. Byman, Gregory Gause, Curt Ryan, Marc Lynch

Three leading political scientists will discuss the regional dimensions of the Syrian conflict.

A light lunch will be served.

Register for this event here.

4. Impressions from North Korea: Insights from two GW Travelers, Monday September 10, 12:30pm-2:00pm, George Washington University

Venue: GW’s Elliot School of International Affairs, 1957 E Street NW, Washington, DC 20052, Room 505

Speakers: Justin Fisher, James Person

The Sigur Center will host a discussion with two members of the GW community who recently returned from North Korea. Justin Fisher and James F. Person will discuss their time teaching and researching, respectively, in North Korea this Summer and impressions from their experiences. Justin Fisher spent a week in North Korea as part of a Statistics Without Borders program teaching statistics to students at Pyongyang University of Science and Technology. James Person recently returned from a two-week trip to North Korea where he conducted historical research.

Register for this event here.

5. America’s Role in the World Post-9/11: A New Survey of Public Opinion, Monday September 10, 12:30pm-2:30pm, Woodrow Wilson Center

Venue: Woodrow Wilson Center, 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20004, 6th Floor, Joseph H. and Claire Flom Auditorium

Speaker: Jane Harman, Marshall Bouton, Michael Hayden, James Zogby, Philip Mudd

This event will launch the latest biennial survey of U.S. public opinion conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, and is held in partnership with them and NPR.

RSVP for this event to rsvp@wilsoncenter.org.

6. Transforming Development: Moving Towards an Open Paradigm, Monday September 10, 3:00pm-4:30pm, CSIS

Venue: CSIS, 1800 K Street NW, Washington, DC 20006, Fourth Floor Conference Room

Speakers: Ben Leo, Michael Elliott, Daniel F. Runde

Please join us for a discussion with Mr. Michael Elliot, President and CEO, ONE Campaign, and Mr. Ben Leo, Global Policy Director, ONE Campaign about their efforts to promote transparency, openness, accountability, and clear results in the evolving international development landscape. As the aid community faces a period of austerity, the panelists will explain how the old paradigm is being replaced by a new, more open, and ultimately more effective development paradigm. Mr. Daniel F. Runde, Director of the Project on Prosperity and Development and Schreyer Chair in Global Analysis, CSIS will moderate the discussion.

RSVP for this event to ppd@csis.org.

7. Campaign 2012: War on Terrorism, Monday September 10, 3:30pm-5:00pm, Brookings Institution

Venue: Brookings Institution, 1775 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036, Falk Auditorium

Speakers: Josh Gerstein, Hafez Ghanem, Stephen R. Grand, Benjamin Wittes

With both presidential campaigns focused almost exclusively on the economy and in the absence of a major attack on the U.S. homeland in recent years, national security has taken a back seat in this year’s presidential campaign. However, the administration and Congress remain sharply at odds over controversial national security policies such as the closure of the Guantanamo Bay detention facility. What kinds of counterterrorism policies will effectively secure the safety of the United States and the world?

On September 10, the Campaign 2012 project at Brookings will hold a discussion on terrorism, the ninth in a series of forums that will identify and address the 12 most critical issues facing the next president. White House Reporter Josh Gerstein of POLITICO will moderate a panel discussion with Brookings experts Benjamin Wittes, Stephen Grand and Hafez Ghanem, who will present recommendations to the next president.

After the program, panelists will take questions from the audience. Participants can follow the conversation on Twitter using hashtag #BITerrorism.

Register for this event here.

8. Democracy & Conflict Series II – The Middle East and Arab Spring: Prospects for Sustainable Peace, Tuesday September 11, 9:30am-11:00am, Johns Hopkins SAIS

Venue: Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, ROME Building, 1619 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036

Speaker: Azizah al-Hibri, Muqtedar Khan, Laith Kubba, Peter Mandaville, Joseph V. Montville

More than a year and a half following the self-immolation of a street vendor in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, Arab nations are grappling with the transition toward sustainable peace. The impact of the Arab Spring movement poses challenges for peaceful elections and establishing stable forms of democratic institutions. This well-versed panel of Middle East and human rights experts will reflect on the relevance and role of Islamic religious values and the influence of foreign policy as democratic movements in the Middle East negotiate their futures.

Register for this event here.

9. Israel’s Security and Iran: A View from Lt. Gen. Dan Haloutz, Tuesday September 11, 9:30am-11:00am, Brookings Institution

Venue: Brookings Institution, 1775 Massachusetts Ave NW, Washington, DC 20036, Falk Auditorium

Speakers: Lt. Gen. Dan Haloutz, Kenneth M. Pollack

While Israel and Iran continue trading covert punches and overheated rhetoric, the question of what Israel can and will do to turn back the clock of a nuclear Iran remains unanswered. Some Israelis fiercely advocate a preventive military strike, while others press just as passionately for a diplomatic track. How divided is Israel on the best way to proceed vis-à-vis Iran? Will Israel’s course put it at odds with Washington?

On September 11, the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings will host Lt. Gen. Dan Haloutz, the former commander-in-chief of the Israeli Defense Forces, for a discussion on his views on the best approach to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. Brookings Senior Fellow Kenneth Pollack will provide introductory remarks and moderate the discussion.

After the program, Lt. Gen. Haloutz will take audience questions.

Register for this event here.

10. Montenegro’s Defense Reform: Cooperation with the U.S., NATO Candidacy and Regional Developments, Tuesday September 11, 10:00am-11:30am, Johns Hopkins SAIS

Venue: Johns Hopkins Carey Business School, 1625 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036, Room 211/212

Montenegro has been one of the recent success stories of the Western Balkans. Since receiving a Membership Action Plan from NATO in December 2009, in close cooperation with the U.S. it has implemented a series of defense, political, and economic reforms, which were recognized in the Chicago Summit Declaration in May 2012 and by NATO Deputy Secretary General Vershbow in July 2012. Montenegro contributes to the ISAF operation in Afghanistan and offers training support to the Afghan National Security Forces. In June 2012 it opened accession talks with the European Union.

Register for this event here.

11. Inevitable Last Resort: Syria or Iran First?, Tuesday September 11, 12:00pm-2:00pm, The Potomac Institute for Policy Studies

Venue: The Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 901 N. Stuart Street, Arlington, VA 22203, Suite 200

Speakers: Michael S. Swetnam, James F. Jeffrey, Barbara Slavin, Theodore Kattouf, Gen Al Gray

Does the expanding civil war in Syria and its grave humanitarian crisis call for immediate international intervention? Will Iran’s potential crossing of a nuclear weapon “red line” inevitably trigger unilateral or multilateral military strikes? Can diplomacy still offer urgent “honorable exit” options and avoid “doomsday” scenarios in the Middle East? These and related issues will be discussed by both practitioners and observers with extensive experience in the region.

RSVP for this event to icts@potomacinstitute.org or 703-562-4522.

12. Elections, Stability, and Security in Pakistan, Tuesday September 11, 3:30pm-5:00pm, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Venue: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1779 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036

Speakers: Frederic Grare, Samina Ahmed

With the March 2013 elections approaching, the Pakistani government has an opportunity to ensure a smooth transfer of power to the next elected government for the first time in the country’s history. Obstacles such as a lack of security, including in the tribal borderlands troubled by militant violence, and the need to ensure the participation of more than 84 million voters threaten to derail the transition. Pakistan’s international partners, particularly the United States, will have a crucial role in supporting an uninterrupted democratic process.

Samina Ahmed of Crisis Group’s South Asia project will discuss ideas from her new report. Carnegie’s Frederic Grare will moderate.

Register for this event here.

13. Islam and the Arab Awakening, Tuesday September 11, 7:00pm-8:00pm, Politics and Prose

Venue: Politics and Prose, 5015 Connecticut Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20008

Speaker: Tariq Ramadan

Starting in Tunisia in December 2010, Arab Spring has changed the political face of a broad swath of countries. How and why did these revolts come about–and, more important, what do they mean for the future? Ramadan, professor of Islamic Studies at Oxford and President of the European Muslim Network, brings his profound knowledge of Islam to bear on questions of religion and civil society.

14. Beijing as an Emerging Power in the South China Sea, Wednesday September 12, 10:00am, The House Committee on Foreign Affairs

Venue: The House Committee on Foreign Affairs, 2170 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515

Speakers: Bonnie Glaser, Peter Brookes, Richard Cronin

Oversight hearing.

15. The Caucasus: A Changing Security Landscape, Thursday September 13, 12:30pm-4:30pm, CSIS

Venue: CSIS, 1800 K Street NW, Washington, DC 20006, B1 Conference Center

Speakers: Andrew Kuchins, George Khelashvili, Sergey Markedonov, Scott Radnitz, Anar Valiyey, Mikhail Alexseev, Sergey Minasyan, Sufian Zhemukhov

The Russia-Georgia war of August 2008 threatened to decisively alter the security context in the Caucasus. Four years later, what really has changed? In this conference, panelists assess the changing relations of the three states of the Caucasus — Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan — with each other and major neighbors, Russia and Iran. They also explore innovative prospects for resolution in the continued conflicts over Abkhazia and South Ossetia and the possibility of renewed hostilities over Nagorno-Karabakh. This conference is based on a set of new PONARS Eurasia Policy Memos, which will be available at the event and online at www.ponarseurasia.org. Lunch will be served.

RSVP for this event to REP@csis.org.

16. Author Series Event: Rajiv Chandrasekaran, “Little Afghanistan: The War Within the War for Afghanistan”, Thursday September 13, 6:30pm-8:30pm, University of California Washington Center

Venue: University of California Washington Center, 1608 Rhode Island Ave NW, Washington, DC 20036

Speaker: Rajiv Chandrasekaran

In the aftermath of the military draw-down of US and NATO forces after over ten years in Afghanistan, examinations of US government policy and efforts have emerged. What internal challenges did the surge of US troops encounter during the war? How was the US aiding reconstruction in a region previously controlled by the Taliban?

Rajiv Chandrasekaran will discuss his findings to these questions and US government policy from the perspective of an on-the-ground reporter during the conflict. This forum will shed light on the complex relationship between America and Afghanistan.

Register for this event here.

Reconciliation: a new vision for OSCE?

I am speaking at the OSCE “Security Days” today in Vienna on a panel devoted to this topic. Here is what I plan to say, more or less:

Reconciliation is hard. Do I want to be reconciled to someone who has done me harm? I may want an apology, compensation, an eye for an eye, but why would I want to be reconciled to something I regard as wrong, harmful, and even evil?

At the personal level, I may be able to escape the need for reconciliation. I can harbor continuing resentment, emigrate, join a veterans’ organization and continue to dislike my enemy. I can hope that my enemy is prosecuted for his crimes and is sent away for a long time. I don’t really have to accept his behavior. Many don’t.

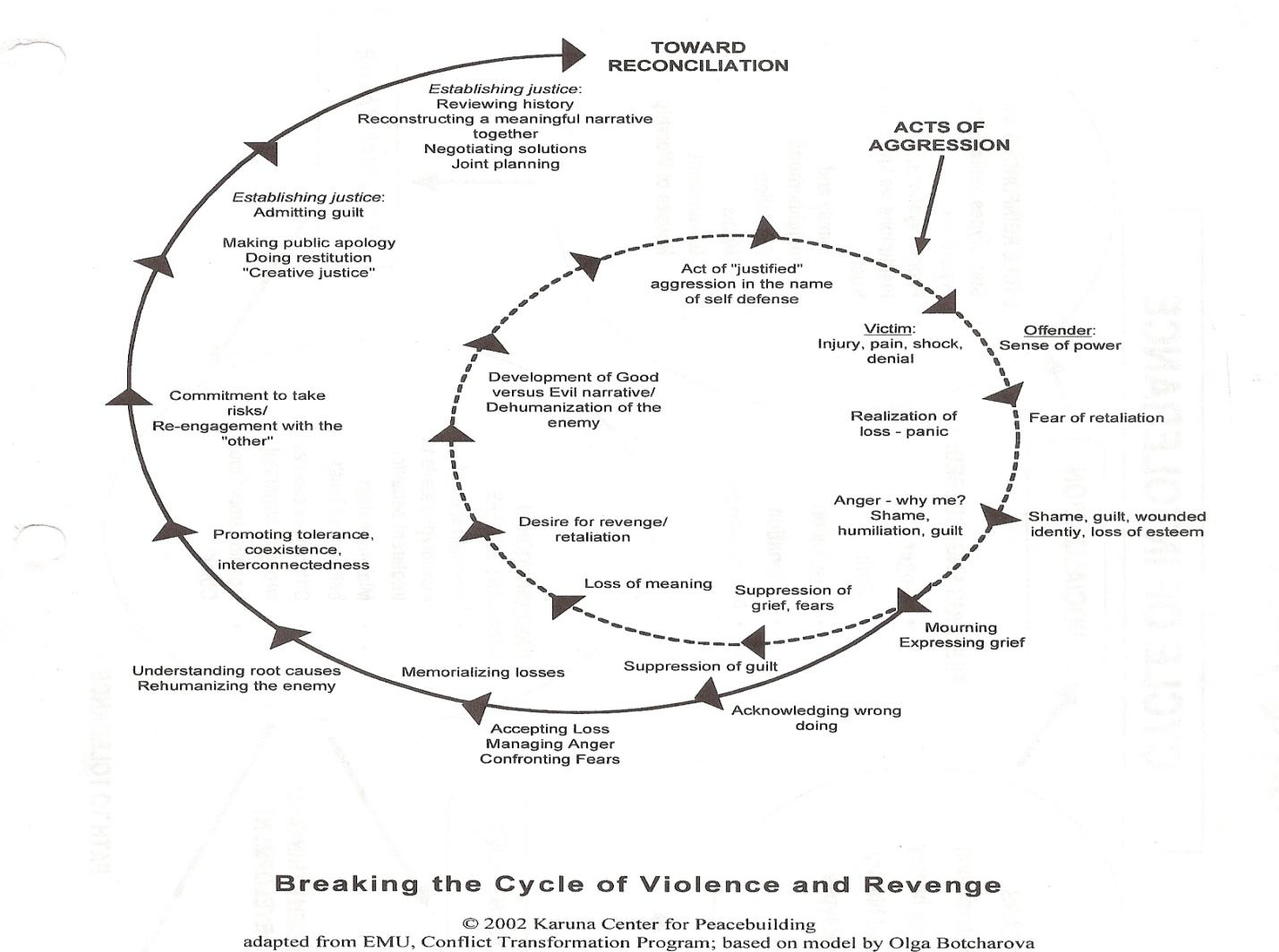

But at the societal level lack of reconciliation has consequences. It is a formula for more violence. We remain trapped in the inner circle of this classic diagram, in a cycle of violence. Victims, feeling loss and desire for revenge, end up attacking those they believe to be perpetrators, who eventually react with violence:

What takes us out of the cycle of violence and retaliation? The critical step is acknowledging wrong doing, a step full of risk for perpetrators and meaning for victims. But once wrong doing is acknowledged, victims can begin to accept loss, manage anger and confront fears. This initiates a virtuous cycle of mutual understanding, re-engagement, admission of guilt, steps toward justice and writing a common history.

What has all this got to do with OSCE? Some OSCE countries are still stuck in the inner cycle of violence, despite dialogue focused on practical confidence-building measures that moves the parties closer. But the vital step of acknowledging wrong has either been skipped entirely or given short shrift. Conflict management is a core OSCE function. The job will not be complete until OSCE re-discovers its role in reconciliation.

I know the Balkans best. We aren’t past the step of acknowledging wrongdoing in Bosnia and Kosovo. Even Greece and Macedonia are trapped in a cycle that could become violent. The situation is less than fully reconciled in Turkey, the Caucasus, Moldova and I imagine other places I know less well. Is there a good example of Balkans reconciliation? The best I know is Montenegro’s apology to Croatia for shelling Dubrovnik. That allowed them to build the positive relationship they have today.

Should reconciliation be a new OSCE vision? Its leadership and member states will decide, but here are questions I would ask if I were considering the proposition:

- How pervasive is the need for reconciliation in the OSCE?

- Would it make a real difference if reconciliation could be established as a norm?

- If it did become a new norm, how would we know when it is achieved?

- What would we do differently from what we do today?

I was in Kosovo earlier this month. There is little sign there of reconciliation: it is difficult for Belgrade and Pristina to talk with each other, they have reached agreements under pressure that are largely unimplemented, OSCE and other international organizations maintain operations there because of the risk of violence. There is little acknowledgement of wrong doing. The memorials are all one-sided: I drove past many well-marked KLA graveyards. We have definitely not reached the outer circle yet.

Would it make a difference if there were acknowledgement of wrong doing? Yes, it would. It would have to be mutual, since a good deal of harm has been done on both sides, even if the magnitude of the harm differs. Self-sustaining security in Kosovo will not be possible until that step has been taken. I would say the same thing about Bosnia, Kyrgystan, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Turkey and Armenia. Your North African partners might benefit from focus on reconciliation.

Dialogue is good. Reconciliation is better. Maybe OSCE should take the next difficult but logical step.

Democracy fails between elections

Newly arrived Middle East Institute summer intern Ilona Gerbakher writes:

While the world is significantly more democratic today than it was twenty years ago, there have been notable failed transitions. Political scientists Danielle Lussier and Jody Laporte gave a joint talk Tuesday at the Woodrow Wilson Center on “The Failure of Democracy in Post-Soviet Eurasia.” Lussier focused on the regression to authoritarian rule in Russia under Vladimir Putin. Laporte investigated the ways in which three post-Soviet authoritarian regimes – Georgia, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan – deal with political opposition between elections. Lussier and Laporte chart the decline of freedom in former communist countries, and ask the question, “why did democracy fail to survive in Russia and the Eurasian republics?”

The case of Russia is perplexing, as it is an outlier in the context of democratization theory. Its level of wealth, education and history of independent statehood suggest Russia should be more politically open than it is today. Lussier presented a graph which showed that, since 1998, Russia’s domestic policies have been backsliding into authoritarian territory. Examples of this backsliding include passage of laws that have obstructed the formation of political parties, cancellation of elections and legislation that curtails freedoms of press and association.

Lussier rejects the three common explanations for the return to authoritarianism in Russia. First of these is that Russia’s elite is insulated from popular pressure by hydrocarabon wealth. Second is that Russia’s history instilled a cultural preference for authoritarian rule. Third is that the failure of liberalization in the 1990’s discredited democracy in Russia.

She suggests an alternative explanation: that the Russian public failed to constrain the Russian political elite. Elite constraining activities, such as building and supporting opposition parties and campaigns as well as public acts of political dissent, are a vital check on the tendency of governments to centralize power in economically or politically difficult periods. The Russian public more consistently engages in elite-enabling activities that support hegemonic parties.

One elite-enabling activity, contacting public officials to perform private favors, is the single (non-voting) political activity with the highest public participation. Other forms of non-voting political participation have steadily declined for the last two decades. They are episodic rather than repetitive. Young people are the least politically engaged sector of society. The decline in political participation preceded the decline in political openness (and the rise of authoritarianism) in Russia.

Laporte shifted the focus from Russia to Georgia, Azerbaijan and Kazakstan. Twenty years after the fall of the Soviet Union, the only post-Soviet democracies are Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The rest are non-democracies, because vote fraud and voter manipulation is endemic. Elections are neither free nor fair. In order to investigate the inner-working of these authoritarian regimes, Laporte examined the way that they treat political opposition between, as well as during, elections.

In all three countries, the election committees are dominated by pro-government officials, state resources are abused in order to mobilize support for the government, and vote fraud is endemic. Opposition parties are prevented from registration in various ways, their space for campaigning is limited, and opposition party operatives are often harassed.

Between election cycles differences emerge. In Kazakhstan, repression of opposition parties is constant and unconditional. All opposition groups and operatives are targeted, the dominant tactic is violent repression, and the goal of the government seems to be to completely eradicate the opposition. In Georgia, repression of opposition parties between elections is intermittent, the targets are random, the dominant tactic of repression is public and private criticism by government officials (acts of violence against opposition groups are rare), and the intent seems to be harassment rather then eradication of the opposition. In Azerbaijan, repression of opposition parties is reactive and the targets are contingent upon circumstances, with more opposition parties are being targeted in recent years. The main goal is to discourage criticism of the government. The dominant tactic is judicial, such as high court fines levied against protestors. Why do we see these differences in the treatment of opposition groups? Laporte speculates that both the nature of the opposition party and patterns of political corruption are at play.

What threatens the United States?

The Council on Foreign Relations published its Preventive Priorities Survey for 2012 last week. What does it tell us about the threats the United States faces in this second decade of the 21st century?

Looking at the ten Tier 1 contingencies “that directly threaten the U.S. homeland, are likely to trigger U.S. military involvement because of treaty commitments, or threaten the supplies of critical U.S. strategic resources,” only three are defined as military threats:

- a major military incident with China involving U.S. or allied forces

- an Iranian nuclear crisis (e.g., surprise advances in nuclear weapons/delivery capability, Israeli response)

- a U.S.-Pakistan military confrontation, triggered by a terror attack or U.S. counterterror operations

Two others might also involve a military threat, though the first is more likely from a terrorist source:

- a mass casualty attack on the U.S. homeland or on a treaty ally

- a severe North Korean crisis (e.g., armed provocations, internal political instability, advances in nuclear weapons/ICBM capability)

The remaining five involve mainly non-military contingencies:

- a highly disruptive cyberattack on U.S. critical infrastructure (e.g., telecommunications, electrical power, gas and oil, water supply, banking and finance, transportation, and emergency services)

- a significant increase in drug trafficking violence in Mexico that spills over into the United States

- severe internal instability in Pakistan, triggered by a civil-military crisis or terror attacks

- political instability in Saudi Arabia that endangers global oil supplies

- intensification of the European sovereign debt crisis that leads to the collapse of the euro, triggering a double-dip U.S. recession and further limiting budgetary resources

Five of the Tier 2 contingencies “that affect countries of strategic importance to the United States but that do not involve a mutual-defense treaty commitment” are also at least partly military in character, though they don’t necessarily involve U.S. forces:

- a severe Indo-Pak crisis that carries risk of military escalation, triggered by major terror attack

- rising tension/naval incident in the eastern Mediterranean Sea between Turkey and Israel

- a major erosion of security and governance gains in Afghanistan with intensification of insurgency or terror attacks

- a South China Sea armed confrontation over competing territorial claims

- a mass casualty attack on Israel

But Tier 2 also involves predominantly non-military threats to U.S. interests, albeit with potential for military consequences:

- political instability in Egypt with wider regional implications

- an outbreak of widespread civil violence in Syria, with potential outside intervention

- an outbreak of widespread civil violence in Yemen

- rising sectarian tensions and renewed violence in Iraq

- growing instability in Bahrain that spurs further Saudi and/or Iranian military action

Likewise Tier 3 contingencies “that could have severe/widespread humanitarian consequences but in countries of limited strategic importance to the United States” include military threats to U.S. interests:

- military conflict between Sudan and South Sudan

- increased conflict in Somalia, with continued outside intervention

- renewed military conflict between Russia and Georgia

- an outbreak of military conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, possibly over Nagorno Karabakh

And some non-military threats:

- heightened political instability and sectarian violence in Nigeria

- political instability in Venezuela surrounding the October 2012 elections or post-Chavez succession

- political instability in Kenya surrounding the August 2012 elections

- an intensification of political instability and violence in Libya

- violent election-related instability in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- political instability/resurgent ethnic violence in Kyrgyzstan

I don’t mean to suggest in any way that the military is irrelevant to these “non-military” threats. But it is not the only tool needed to meet these contingencies, or even to meet the military ones. And if you begin thinking about preventive action, which is what the CFR unit that publishes this material does, there are clearly major non-military dimensions to what is needed to meet even the threats that take primarily military form.

And for those who read this blog because it publishes sometimes on the Balkans, please note: the region are nowhere to be seen on this list of 30 priorities for the United States.

Next week’s “peace picks”

Good stuff, especially early in the week. Heavy on Johns Hopkins events, but what do you expect?

1. Strengthening the Armenianj-Azerbaijani Track II Dialogue, Carnegie Endowment, October 17, 10-11:45 am

With Philip Gamaghelyan, Tabib Huseynov, and Thomas de Waal

With the main diplomatic track negotiating the conflict over Nagorny Karabakh apparently deadlocked, more attention is being focused on how tension can be reduced and bridges built through Track II initiatives and dialogue between ordinary Armenians and Azerbaijanis.

Mohamed Salah Tekaya, Tunisian ambassador to the United States; Tamara Wittes, deputy assistant secretary for Near Eastern Affairs and deputy special coordinator for Middle East Transitions at the U.S. Department of State; Mohamed Ali Malouche, president of the Tunisian American Young Professionals; and Kurt Volker (moderator), managing director of CTR, will discuss this topic. For more information and to RSVP, visit http://www.eventbrite.com/event/2279443878/mcivte

4. Mexico and the War on Drugs: Time to Legalize, former Mexican President Vicente Fox, held at Mount Vernon Place, Center for Global Liberty and Prosperity, Cato Institute, to be held at the Undercroft Auditorium, 900 Massachusetts Ave., N.W. October 18, noon

Mexico is paying a high price for fighting a war on drugs that are consumed in the United States. More than 40,000 people have died in drug-related violence since the end of 2006 when Mexico began an aggressive campaign against narco-trafficking. The drug war has led to a rise in corruption and gruesome criminality that is weakening democratic institutions, the press, law enforcement, and other elements of a free society. Former Mexican president Vicente Fox will explain that prohibition is not working and that the legalization of the sale, use, and production of drugs in Mexico and beyond offers a superior way of dealing with the problem of drug abuse.

To register for this event, email events@cato.org, fax (202) 371-0841, or call (202) 789-5229 by noon, Monday, October 17, 2011.

Monday, October 17, 2011

7:30 PM – 9:00 PM

Lindner Family Commons, Room 602

1957 E Street, NW

5. Revolutionary vs. Reformist Islam: The Iran-Turkey Rivalry in the Middle East, Lindner Family Commons, room 602, 1957 E St NW, October 18, 7:30-9 pm

Ömer Tapinar, Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution

Hadi Semati, Iranian Political Scientist

Mohammad Tabaar, Adjunct Lecturer, GW

The Arab Spring has brought Iran and Turkey into a regional rivalry to sell their different brands of Islam. While Tehran is hoping to inspire an “Islamic awakening”, Ankara is calling for a “secular state that respects all religions.” The panelists will discuss this trend and its influences on domestic politics in Iran and Turkey.

The Middle East Policy Forum is presented with the generous support of ExxonMobil.

This program will be off the record out of respect for its presenters.

RSVP at: http://tinyurl.com/3ntfx9o

Sponsored by the Institute for Middle Eastern Stuides

PS: I really should not have missed this Middle East Institute event:

Troubled Triangle: The US, Turkey, and Israel in the New Middle East, Stimson Center, 1111 19th St NW, 11th floor, October 18, 4:30-6 pm

The trilateral relationship between Turkey, Israel and the United States has deteriorated in recent years as Israel’s and Turkey’s foreign policy goals in the Middle East continue to diverge. Despite repeated attempts, the United States has failed to reconcile these two important regional allies since the divisive Mavi Marmara incident in May 2010. Please join us for a discussion of this critical yet troubled trilateral relationship in a time of unprecedented change in the Middle East. The discussion will feature Prof. William B. Quandt, Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., Professor of Politics at University of Virginia, Lara Friedman, Director of Policy and Government Relations and Gönül Tol, Executive Director of MEI Center for Turkish Studies, and will be held on October 18 at the Henry L. Stimson Center.

A helpful reminder of the Ottoman Empire

Why is this helpful? Because it illustrates how many of today’s enduring conflicts–not only those termed “Middle Eastern”–are rooted in the Ottoman Empire and its immediate neighborhood: Bosnia, Kosovo, Greece/Turkey, Armenia/Azerbaijan, Israel/Arabs (Palestine, Syria, Lebanon), Iraq, Iraq/Iran, Shia (Iran)/Sunni (Saudi Arabia, Egypt), North/South Sudan, Yemen.

Ottoman success in managing the many ethnic and sectarian groups inhabiting the Empire, without imposing conformity to a single identity (and without providing equal rights) has left the 21st century with problems it finds hard to understand, never mind resolve.

In much of the former Ottoman Empire, many people refuse to be labeled a “minority” just because their numbers are fewer than other groups, states are regarded as formed by ethnic groups rather than by individuals, individual rights are often less important than group rights and being “outvoted” is undemocratic.

A Croat leader in Bosnia told me 15 years ago that one thing that would never work there was “one man, one vote.” It just wasn’t their way of doing things. For a decision to be valid, a majority of each ethnic group was needed , not a majority of the population as a whole.

In a society of this sort, a boycott by one ethnic group is regarded as invalidating a decision made by the majority: the Serbs thought their boycott of the Bosnia independence referendum should have invalidated it, but the European Union had imposed a 50 per cent plus one standard. There lie the origins of war.

The question of whether Israel is a Jewish state is rooted in the same thinking that defined Yugoslavia as the kingdom of the Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, and it bears a family resemblance to the thinking behind “Greater Serbia” and “Greater Albania.” If it is the ethnic group that forms the state, why should there be more than one state in which that ethnic group lives?

Ours is a state (yes, that is the proper term for what we insist on calling the Federal Government) built on a concept of individual rights, equal for all. The concept challenges American imaginations from time to time: certainly it did when Truman overcame strong resistance to integrate the US Army, and it is reaching the limits of John McCain’s imagination in the debate over “don’t ask, don’t tell.” But the march of American history is clearly in the direction of equal individual rights.

That is a direction many former Ottoman territories find it difficult to take, because some groups have more substantial rights than others; even when the groups’ rights are equal, they can veto each other. A lot of the state-building challenge in those areas arises from this fundamental difference.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts