Tag: Balkans

A milestone, again

Today is Vidovdan, Saint Vitus’ Day for Serbs. It is the 623rd anniversary of the battle of Kosovo Polje, commemorated as a religio-national holiday by Serbs worldwide. It is also the date on which Gavrilo Princip assassinated the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, precipitating World War I, as well as other major events in Serbian history.

Today there is one more: newly elected nationalist Tomislav Nikolic asked nationalist Ivica Dacic, leader of Slobodan Milosevic’s Socialist party, to form a new government, with the support of Nikolic’s own Progressive party as well as several smaller parties in the governing coalition.

There is nothing socialist about Dacic or progressive about Nikolic. Both are nationalists and pragmatists who draw support from an electorate disappointed in the performance of the more moderate nationalist Boris Tadic, who lost this month’s presidential election after more than seven years at the helm. All claim to be pro-European, but Tadic more loudly, definitively and effectively than Nikolic and Dacic.

Alternation in power is a vital part of democratic governance. Dacic participated as Interior Minister in Tadic’s last government, but Nikolic and his “progressives” are new to governing responsibility. It is a sign of the maturity of Serb’s still young democracy that the international community is taking Nikolic’s accession to power in stride, even if many might have preferred that Tadic win.

Both Nikolic and Dacic have already gone out of their way to consult with Moscow during the government formation process. That gives more than a hint of where they plan to steer Serbia, which even under Tadic has flirted with Russia and vaunted itself as non-aligned (whatever that means in the post-Cold War world).

What does this augur for Washington and Brussels? For Brussels, it likely means a deceleration in Serbia’s technical preparations for European Union membership, which proceeded apace under Tadic. A slow-down won’t cause any handwringing in Brussels, where the prospect of any new members before 2020 is unwelcome. The EU will want to keep Serbia on track for eventual membership, but it likely will feel far less pressure to offer a date to begin accession negotiations with a Dacic-led government.

That’s a good thing from Washington’s perspective. Serbia continued under Tadic to monkey in Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as in Kosovo in unhelpful ways. Washington was hesitant to ask too much of Tadic, who argued that would strengthen his more nationalist competitors. A tougher EU stance is vital to moderating Serbia’s efforts to maintain strictly separate governing structures in both Bosnia’s Republika Srpska and northern Kosovo.

The day also saw the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia throw out one charge of genocide against Bosnian Serb wartime leader Radovan Karadzic. I hope this is seen in Bosnia and Serbia as evidence that he is getting a fair trial.

More important was the decision on Tuesday in a Serbian court finding 14 people guilty of killing civilians in late 1991, during Serb efforts to seize parts of Croatian territory and cleanse it of Croats. As I argued at the OSCE earlier this week, acknowledgement of responsibility for wrongdoing is a key step in reconciliation. If the new nationalist leadership in Belgrade plays it right, the Serbian courts have given them an opening to acknowledge the past and by doing so improve relations between Serbia and its neighbors in the future.

Reconciliation: a new vision for OSCE?

I am speaking at the OSCE “Security Days” today in Vienna on a panel devoted to this topic. Here is what I plan to say, more or less:

Reconciliation is hard. Do I want to be reconciled to someone who has done me harm? I may want an apology, compensation, an eye for an eye, but why would I want to be reconciled to something I regard as wrong, harmful, and even evil?

At the personal level, I may be able to escape the need for reconciliation. I can harbor continuing resentment, emigrate, join a veterans’ organization and continue to dislike my enemy. I can hope that my enemy is prosecuted for his crimes and is sent away for a long time. I don’t really have to accept his behavior. Many don’t.

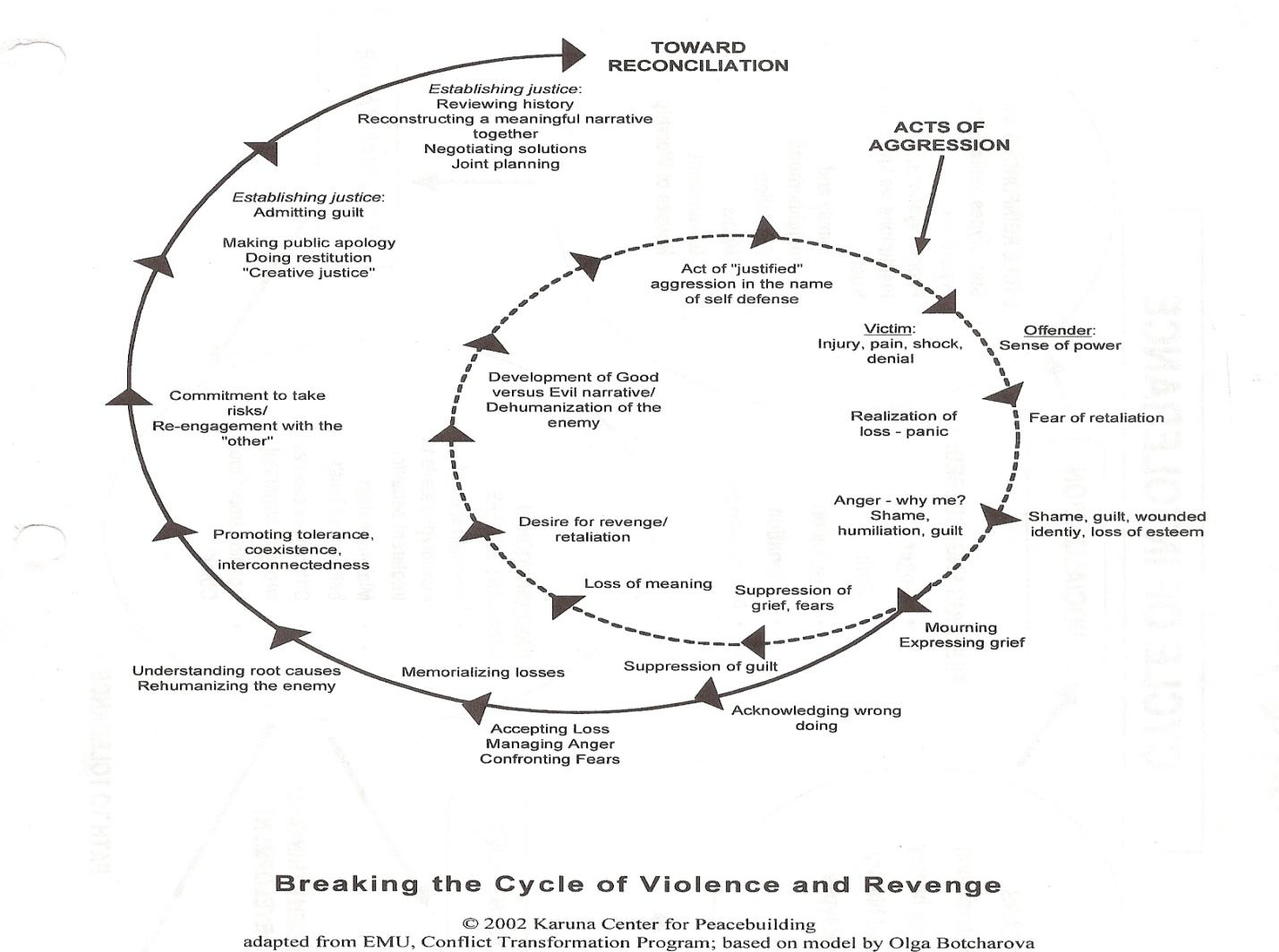

But at the societal level lack of reconciliation has consequences. It is a formula for more violence. We remain trapped in the inner circle of this classic diagram, in a cycle of violence. Victims, feeling loss and desire for revenge, end up attacking those they believe to be perpetrators, who eventually react with violence:

What takes us out of the cycle of violence and retaliation? The critical step is acknowledging wrong doing, a step full of risk for perpetrators and meaning for victims. But once wrong doing is acknowledged, victims can begin to accept loss, manage anger and confront fears. This initiates a virtuous cycle of mutual understanding, re-engagement, admission of guilt, steps toward justice and writing a common history.

What has all this got to do with OSCE? Some OSCE countries are still stuck in the inner cycle of violence, despite dialogue focused on practical confidence-building measures that moves the parties closer. But the vital step of acknowledging wrong has either been skipped entirely or given short shrift. Conflict management is a core OSCE function. The job will not be complete until OSCE re-discovers its role in reconciliation.

I know the Balkans best. We aren’t past the step of acknowledging wrongdoing in Bosnia and Kosovo. Even Greece and Macedonia are trapped in a cycle that could become violent. The situation is less than fully reconciled in Turkey, the Caucasus, Moldova and I imagine other places I know less well. Is there a good example of Balkans reconciliation? The best I know is Montenegro’s apology to Croatia for shelling Dubrovnik. That allowed them to build the positive relationship they have today.

Should reconciliation be a new OSCE vision? Its leadership and member states will decide, but here are questions I would ask if I were considering the proposition:

- How pervasive is the need for reconciliation in the OSCE?

- Would it make a real difference if reconciliation could be established as a norm?

- If it did become a new norm, how would we know when it is achieved?

- What would we do differently from what we do today?

I was in Kosovo earlier this month. There is little sign there of reconciliation: it is difficult for Belgrade and Pristina to talk with each other, they have reached agreements under pressure that are largely unimplemented, OSCE and other international organizations maintain operations there because of the risk of violence. There is little acknowledgement of wrong doing. The memorials are all one-sided: I drove past many well-marked KLA graveyards. We have definitely not reached the outer circle yet.

Would it make a difference if there were acknowledgement of wrong doing? Yes, it would. It would have to be mutual, since a good deal of harm has been done on both sides, even if the magnitude of the harm differs. Self-sustaining security in Kosovo will not be possible until that step has been taken. I would say the same thing about Bosnia, Kyrgystan, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Turkey and Armenia. Your North African partners might benefit from focus on reconciliation.

Dialogue is good. Reconciliation is better. Maybe OSCE should take the next difficult but logical step.

Albania’s role in the neighborhood

I spoke this morning at CSIS on this topic. Here are the notes I prepared for myself:

- In an important sense, Albania is the new guy on the Balkans block. It was thoroughly isolated from 1945 through the Cold War.

- The collapse of the Communist regime was cataclysmic for Albanians. I was in charge of the U.S. Embassy in Rome in August 1991 when the Vlora, a ship carrying 10,000 refugees, reached the port of Bari.

- Twice in the 1990s Italian troops were sent to Albania on what we would now call stabilization missions.

- When I went to observe the 1997 elections, I found myself in the midst of far more gunfire at night than in Sarajevo during the war.

- Less than 15 years later, Albania is a NATO member and sends peacekeepers abroad. It is an exporter of stability rather than an importer.

- Still the poorest country in Europe, Albania has suffered a slowdown in growth since the 2008 but weathered the financial crisis relatively well. Severe poverty is down sharply.

- Its role in the neighborhood is a positive one: Albania’s relations with neighbors Montenegro, Serbia, Kosovo, Macedonia and Greece are generally very good.

- This is a remarkable achievement, one that merits a gold star no matter what I say farther on.

- There are problems. Albania’s problems are above all internal: its politics are contentious and sometimes violent, its public administration is weak, its economy is burdened with corruption and organized crime, rule of law is unreliable.

- These are all well-known and longstanding problems that will need to be addressed in the EU accession process, which has begun in recent years with the application for membership, the visa waiver and the Stabilization and Association Agreement, even if Brussels has not given Tirana candidate status or a date for negotiations to begin.

- I really see only one thing that could derail Albania’s progress towards European Union membership, if not in this decade then in the next one.

- That is its relationship with other Albanian populations in the Balkans. Fundamentally, it boils down to this: will the Albanians of the Balkans accept living in six different countries, or will they challenge the existing territorial arrangements?

- If I were in their shoes, I would not for a moment put at risk my hopes to be inside the European Union by unsettling borders in the Balkans or fooling with irredentist ambitions.

- Washington and Brussels will be unequivocal in rejecting Greater Albania ambitions, which could lead to catastrophic population movements and widespread instability.

- The wise course for Albania is to cure its internal ills, maintain good relations with all its neighbors, including Italy as well as those in the Balkans, and maintain close cultural ties with Albanians who live in other countries, including the United States.

- That Albania will continue to export stability, enjoy improving prosperity and enter the European Union with its double-headed eagle held high.

PS: A lot of people in the room, including the Albanian ambassador, thought Greater Albania was getting too much attention in the discussion. I trust they are right. The attention clearly reflects how strongly Americans feel the idea is a bad one, not how strongly Albanians are attached to it.

Mendacious

As regular readers will have noticed, I’ve avoided writing about the Balkans lately. There are a lot more interesting things going on elsewhere in the world. But Greece’s decision to put stickers reading “recognized by Greece as FYROM” over the MK on newly issued Macedonian license plates is too fine an opportunity to pass up.

Greece is doing this allegedly under the 1995 interim agreement with the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM), whose application for NATO membership Athens has blocked, first in Bucharest in 2008. Greece repeated its move more recently in Chicago this year, despite an International Court of Justice (ICJ) decision unequivocal in finding Greece in violation of the agreement in Bucharest.

Where I come from, if you want to apply an agreement you have to fulfill its terms yourself first. Greece understands this perfectly well and accused Macedonia of being in violation of the interim agreement during the ICJ proceedings. Its accusations were found to lack serious merit. Now Athens, having been found in violation, is seeking to apply the agreement it refused to apply in Chicago.

Words fail me. Mendacious maybe. They have apparently failed Skopje as well, which in the initial press report is said to be weighing its response. That’s wise. There is really no point in aggravating the situation further, tempting though it may be to do so.

But I’m not a government. I’m a blogging/tweeting professor and can suggest anything I like. I only risk hate tweets and emails. Maybe a sticker to cover the GR on Greek plates that reads “Southern Macedonia”? Or one that says “I am Greek traveling in a country whose name I don’t accept”? Ethnic Macedonians and Albanians with Greek license plates would have to be exempt from that one. Or one that declares “interim agreement be damned”?

Here in DC, most license plates read “taxation without representation,” because residents of the District of Columbia pay Federal taxes but have a representative in Congress who can’t vote in plenary (and no senators–even states smaller in population than DC are entitled to two).

Slogans of all sorts grace the license plates of most cars in the United States. I’ve always thought it unimaginative of Europeans not to use that bit of valuable real estate on the back of a car for something edifying. My favorite proposal (it isn’t reality) was for Wisconsin, a big dairy producing state: “eat cheese or die” (New Hampshire’s plates really do read “live free or die”).

Greece of course has bigger problems these days than the “MK” on its northern neighbor’s license plates. It would do well to save a few euros by cutting the funding for those “recognized as FYROM” stickers. It would do even better to stop violating an agreement it wants to apply and allow FYROM to enter NATO.

Nikolic starts well, now let’s have fun

Tomislav Nikolic’s inauguration as President of Serbia went well: he pledged Serbia to a European future, committed himself to resolving regional problems through dialogue and promised future prosperity in return for hard work. He did not of course repeat his controversial remarks of recent days seeming to justify the Serb assault in the early 1990s on the Croatian town of Vukovar and his denial of genocide at the Bosnian town of Srebrenica.

He did however necessarily commit himself to

protect the Constitution, respect and safeguard the territorial integrity of Serbia and try to unite all political forces in the country in order to identify and implement a common policy on the issue of Kosovo-Metohija.

This means that he maintains Serbia’s claim to all of Kosovo, despite loss of control over 89% of its territory and more or less the same percentage of its population. As required by the constitution, he denies the validity of the 2008 declaration of independence and recognition by 90 sovereign states.

The key question for today’s Serbia is whether and how Nikolic resolves the contradiction between his commitment to a European future for his country and his commitment to holding on to Kosovo. No Serb politician wants to admit that this contradiction exists, but it does and they all know it. Twenty-two European Union members have recognized Kosovo’s independence. They will be unwilling to accept Serbia into their club unless it accepts Kosovo’s sovereignty and establishes “good neighborly relations” with the democratically validated authorities in Pristina.

Belgrade has been inclined to put off any resolution of this contradiction for as long as possible. That is understandable. It involves a trade-off that is unappetizing: either give up Kosovo, or give up the EU.

But the failure to make a clear choice distorts judgment on other issues important to Serbia’s future: relationships with Russia, the United States and NATO as well as Serbia’s relationship with Kosovo’s Albanian citizens (Kosovo’s Serb citizens will presumably choose to remain Serbian citizens, though some have also accepted Kosovo citizenship).

The United States and the EU have been reluctant to press Serbia hard on its choice between the EU and Kosovo, for fear of undermining former President Boris Tadic and strengthening Nikolic’s more nationalist forces. It might appear that there is no longer need for that reluctance with Nikolic in the presidency. But there is a real possibility that Tadic will become prime minister and lead the first government of Nikolic’s mandate. That would enable Serbia to renew its diplomatic manipulation of the West on the Kosovo vs. EU issue.

Nikolic in the past has been more inclined to advocate partition of Kosovo than to give up all claim to it. This proposition won’t go anywhere. The Americans and the Europeans are solidly against it, because it would precipitate a domino-effect of partitions in Macedonia, Bosnia, Cyprus and perhaps farther afield. The Kosovars would ask for the Albanian-majority area of southern Serbia in trade, something Belgrade would not want to offer. More importantly: it is not in the interest of most Serbs who live in Kosovo (outside the northern area Serbia would hope to claim). The Serbian church, whose important sites are all in the south, is solidly opposed.

I’ll hope that Nikolic defies the odds and gets courageous about Kosovo: it is lost to Serbian sovereignty. All politicians in Belgrade, including Nikolic, understand that, but no one wants to accept responsibility for it. Some of my Serb Twitter followers and email correspondents assure me there is not a chance in hell Nikolic will: that’s why they voted for him. They want him to choose Kosovo over the tarnished EU.

They may well be correct, but I’ll wait to see what Nikolic does. His first test will be implementation of the agreements already reached with Pristina. Tadic did precious little to make them operational. If Nikolic wants to stick his predecessor with responsibility for them, he’ll demand that they be implemented by a newly named prime minister, whether it be Tadic or someone else from his Democratic Party.

Nikolic could also change Serbia’s policy on United Nations membership for Kosovo, thus forcing Foreign Minister Vuk Jeremic to preside in his new position as General Assembly president over Pristina’s acceptance into the UN. Watching that would be worth almost any admission price.

I’m not holding my breath for any of this to happen. Just saying it would be fun.

Serbia and Europe, at risk

Sonja Biserko, President of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia and the Eric Lane Fellow at Clare College, University of Cambridge, and Josip Glaurdic, the Junior Research Fellow at Clare College, write:

In an expression of the real spirit of Serbia, Tomislav Nikolić won the presidential election on a wave of popular discontent thanks to a series of blunders by former President Tadić’s Democratic Party. The conservative segment of Serbia’s society and a consolidated populist right are the beneficiaries. The result presents a potentially momentous challenge for Serbia, its neighbors, and the whole of Europe. With Nikolić at its helm, Serbia is now an unreliable partner, save perhaps for Putin’s Russia.

Nikolić’s victory and the strong showing of his Serbian Progressive Party in earlier parliamentary elections have brought the decade-long efforts to keep Serbia on a Euroatlantic course into question. Serbia’s contemporary political climate and its political culture have demonstrated the low achievement of its democratic transition. Since the fall of Slobodan Milošević in October 2000, Serbia has not achieved political consensus regarding its future or its strategic orientation.

In spite of efforts in Brussels to spin Serbia’s electoral results into a “victory of pro-European forces,” these electoral results have exposed as perilously fragile the political engineering that has tried to bind Serbia into European integration. What Serbs term the “grey zone” of their politics – the security apparatus, the current and former military brass, the nationalist intelligentsia – abandoned Tadić because it wanted to slow down Serbia’s European integration and halt the process of coming to terms with Serbia’s recent past. The grey zone will now seek to slow democratic reforms and normalization of relations with the rest of the region. Serbia’s dialogue with Kosovo, its judicial, military, and police reforms, its cooperation with NATO and integration with the EU–already sluggish–will grind to a halt.

The president-elect rushed to announce that his foreign policy will be “both Russia and the EU,” that he will never recognize Kosovo, that he recognizes Montenegro but not the Montenegrins as a nation, and that Serbia does not want NATO membership. His recent statements to Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung recalling Serb ambitions he supported to take Croatian territory serve as a potent reminder of the tragic policies of the 1990s, which could revive under his leadership.

Tadić’s loss jeopardizes the Democratic Party, which faces an identity and leadership crisis similar to the one it faced after the assassination of its leader and Serbia’s Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić in 2003. The Democratic Party could be irreparably damaged as an organizational foundation for reform. The further slowdown, or even reversal, of Serbia’s democratic transformation could frustrate consolidation and democratization in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and Montenegro and even cause regional instability.

A great deal depends on the stance of the EU and the Unites States. The electoral results were an indirect consequence of a subtle, but noticeable, policy shift in Brussels and Washington. The appeal of Tomislav Nikolić among centrist voters (which, at the very least, led to their decision to abstain from voting) arguably had a lot to do with Western signals of approval of his possible victory and of his supposed transformation from a nationalist radical into a pro-European conservative.

Those in Western capitals who crafted such a policy shift seem not to have learned much from recent history. They are bound to be disappointed by Nikolić, just as they were let down by their two other notable “projects” – Serbia’s former Prime Minister Vojislav Koštunica and President of Republika Srpska Milorad Dodik. Serbia and Europe will have to live with Nikolić as president for at least the next five years. If its relationship with Tadić was difficult because of his inability to shed nationalist ballast, Brussels is in for an even more frustrating ride with Nikolić.

European leaders will still have to rise to the challenge and offer a real path to EU integration for all the countries of the Western Balkans, and especially for Serbia’s neighbors. Only a strategy which continuously supports the accession process can ensure that the region, no matter how slowly, moves forward and that the EU maintains its position of influence.

Any sign of a decline in commitment to enlargement by the EU capitals lowers the Union’s influence and, thus also the influence of the truly pro-European forces in politics and society. This could have even more devastating consequences for the democratization and stabilization of the whole region than the election of Tomislav Nikolić.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts